I don’t have a very good relationship with representational art, but yesterday I made an effort, which I report now.

I took two children of a friend to the Met. They are aged twelve and ten years and I don’t know how much time they’ve ever spent in art museums. I have spent a lot of time — too much for my own well-being. The school where I was immured in my teens is in a part of the world so thickly-grown with museums that they became ordinary hang-out places after school. Not naturally sympathetic to visual art, I feel I’ve been overexposed.

And I don’t think I pass muster as museum docent — I find I am not an inspiring explainer of the meaning or importance of art. I have a lot of doubts, myself, about what I see in museums, and that probably affects what I can do for other people.

A work of art has both physical form and some set of messages, intended or unintended. The physical form has technical issues of execution associated with it, but also style, which grades into the area of messages. I’m never sure what interplay there is or should be between my reaction to the physical form and the other matters. And often what I know about the messages — frankly — does not interest me. Compared to such organized abstractions as a well-constructed sonata movement or handwritten kanji, which seize my attention if not my very soul, it’s hard for me to get stirred up about almost any landscape or portrait. I realize saying this may condemn me as a boor, but there it is.

On top of that, in a museum I feel that works of art on formal display seem to insist that I deal with them and decide what I think about them, and their aggressiveness disturbs me. So maybe it is best that I be kept away from the impressionable young.

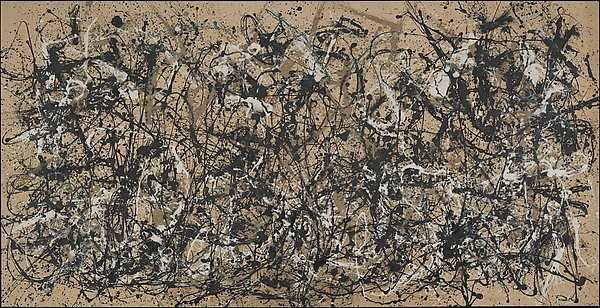

After my charges led me to see some Oceanian ritual objects and Roman statuary, and after we had been disappointed that musical instruments, costumes, and the Temple of Dendur were all closed, I took them to see the Met’s large Jackson Pollack, in the Twentieth Century Art section. (“Autumn Rhythm [Number 30]”)

The reaction was instant. Twelve Years Old sat down in front of the painting and looked at it without interruption. Ten Years Old didn’t waste any time but blurted out from ten feet away, “How is that art?”

All right — I don’t know much about art and what I think I know is probably wrong and in any case I don’t convey it well. But I know something about teaching, and I know how to try to debug a puzzling problem, whether a Classical Chinese sentence or an English poem or a block of code. Analysis comes into it, but so does listening to one’s inner reactions. So I felt summoned to argue.

First, to soften up Ten Years Old I asked him for a definition of art. He didn’t have one ready. That’s a good first step — I don’t have one, either. I admit I’ve had enough years to prepare, but I think I’m in a better state to deal with the confusion that artworks cause me if I don’t have a ready standard to apply to them.

I also asked my charges to look at the painting for a while and see if the way it appeared to them changed at all. And I told them I didn’t think they needed to have an opinion as to whether it was art or not, or good or not, or interesting or not — that day. The picture would be there for a long time and they could spend as long as they needed to think about the question and make up their minds later. I hope they keep thinking about it.

I haven’t made up my mind yet, by the way. That picture has been in the Met or MoMA since I was a boy, and I’m still interacting with it fruitfully. I still don’t know if I like it or not, much less what it means or whether it means anything. I’d say it’s interesting, though.

We tossed around a few possible interpretations. At the end of our time there, we agreed that it could be, in Ten Years Old’s words, “a representation of New York City.”

Twelve Years Old, temperamentally disinclined to disputation, declined to offer any opinions at all. I hope he’s still thinking about it.

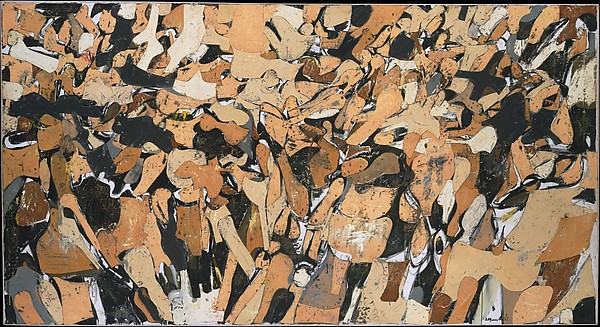

Against the implied claim that the piece is not “art”, I also pointed out that it was placed next to “The Battle” by Conrad Marca-Relli, which I think invites the viewer to consider contrasts and points of concord with the Pollock.

I don’t know where this will lead. I hope to have other chances to interact with them about the Pollock. I don’t care if they like it or understand it — what I fear is that they will fail to challenge their own over-quick analysis of it. I’d like to exert gentle pressure on them to keep engaging with it.

Whether out of laziness or lack of aptitude, I don’t really know anything about art. But I do know that holding a difficulty in mind and continuing to engage with it, emotionally as well as analyticallly, is one way of learning to solve not just that problem but problems in general. And I think that’s a skill worth having — coming face to face with an unexpected painting is a chance to practice it.

[end]